Par Florence Egal et Thomas Forster

Half of the world’s population is presently under lock or stay-at-home orders to prevent the spread of the Covid19 pandemic. Places of social aggregation such as schools, then bars and restaurants, then markets close down. This has obvious implications for food systems in both urban and rural areas. Governments as a rule commit to maintaining essential economic activities and food availability but in most cities food supply depends mainly on food imports which are threatened by restrictions of mobility and closing of borders.

Farming activities, and in particular – often export-driven – intensive agriculture, are facing major constraints. At a time when European and North American countries shift from winter to the spring and summer season, which depends on adding to the agricultural workforce, seasonal – often informal and/or migrant – labourers are no longer available, and disruptions in existing value chains and concerns for their longer-term viability are on the increase.

In many countries short food chains, including urban and peri-urban agriculture are not seen as essential economic activities, and face logistical and organizational challenges. Farmers markets are closed or their access is limited, with impacts on both small-scale farmers and consumers at a time when demand for local, seasonal and organic foods, and in particular fresh fruits and vegetables, is rising in urban consumer groups. And as schools close down, so do school canteens, with consequences both on social protection programmes and on suppliers, including small-scale producers.

While the health situation is of course dramatic and major social problems are emerging, in particular in the informal sector, this unprecedented situation is also generating an extraordinary surge of creativity and innovation to cope with, and adapt to, unexpected constraints. Promising practices are emerging everywhere. These of course vary widely according to the size and resources of cities, as well as local culture and lifestyles, but common threads can be found and can inform a necessary transition towards more resilient food systems and diets and more sustainable development in the post-crisis period.

Closed restaurants reorient their activities towards home-delivery or catering for essential workers (e.g. health staff) and their suppliers shift to alternative retailing practices, such as neighbourhood shops or (again) home-delivery, therefore strengthening linkages between producers and consumers. Social protection programmes organize food distribution at neighbourhood collection centres and solidarity initiatives are emerging everywhere to assist old people or homeless people. Supermarkets are encouraged to purchase unsold food production with a view to limit waste and support farmers.

Consumers – including men and youth – re-discover cooking at home and less processed foods, and junk food is not as easily available given the closure of fast food restaurants. There is a shift away from supermarkets to avoid long queues and local food shops are challenged to respond to the new demand. Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) has to reorganize and reorient distribution systems with priority to home delivery, including for vulnerable households. Food hubs and e-commerce using ICT platforms are providing options for both consumers and producers. In rural areas, there is a revival of small shops and traditional solidarity systems, and some villages perceive the present situation as an opportunity to correct previous dysfunctions.

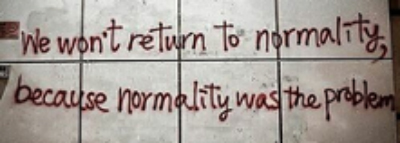

Things that were deemed impossible are happening in the present emergency context. While heads of state make the headlines in the media, local authorities, civil society and private sector join forces and resources to address the situation. Regulations are waived or modified. Information technology has become essential to life in confinement but is also the most effective way to link demand and supply, share experiences, plan and coordinate the emergency response and discuss the post-crisis period. And people have more time to think. The emerging consensus is that the problems that generated the epidemic and its consequences need to be addressed and that there is no going back to the pre-Covid19 situation.

In 2015, about a hundred mayors signed the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact[1] and committed to promote more sustainable food systems. By the time the Covid19 pandemic struck, the number of signatory cities had doubled. Many of the actions recommended in the Framework for Action are actually taking place in the wake of the pandemic. Food has become a priority for both municipal authorities and locked down households and more and more people are becoming active players and citizens rather than passive customers. Some degree of re-localisation of agriculture, with increased production and consumption of local and seasonal foods is acknowledged as an important dimension of resilience and livelihoods. Short food chains and social protection for food access are making the headlines. And the link with climate change and unsustainable agriculture practices is widely acknowledged.

There is a broad consensus that the present pandemic and its impacts reflect to a significant degree dysfunctional policies and an excessive bias towards globalization and privatization in the last decades. Dealing with this crisis therefore offers an opportunity to reorient and rebalance policies and support local action, that brings together the health and food sector, promotes sustainable food production, ensures social justice, and overall accelerates the transition to more resilient territories and sustainable diets. But unless government authorities provide appropriate recognition and support to promising practices – for example short food chains, these run the risk of being victims of their own success. If they are not able to respond to an exploding demand, they will lose credibility and generate frustration. It is essential to learn from the extraordinary social and economic laboratory provided by the Covid19 response and build upon concrete actions towards more sustainable diets.

About the authors

Florence Egal, food security, nutrition and sustainable diets expert was the co-secretary of the Food for Cities initiative in FAO until her retirement in 2013. Since then she provided technical assistance to developing the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, supports UN-Habitat’s initiative on urban-rural linkages and is a member of the FLEdGE sustainable food systems network.

Thomas Forster, food and agriculture policy expert, is the co-author of the report : City Regions as Landscapes for People, Food and Nature published in 2014 by EcoAgriculture Partners. He led the technical teams for the Milan Pact (2015) and the Urban Rural Linkages: Guiding Principles and Framework for Action (2019). He also teaches food policy and governance in the food studies program of the New School for Public Engagement in New York.

[1] http://www.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Milan-Urban-Food-Policy-Pact-EN.pdf